Cutting Loan Approval Time By 65% Using Flow Thinking

Background

At the start, the approval process took 50 to 60 days from start to finish. That’s roughly two months for a customer to get access to money they were promised.

The team was smart but none of them had any background in agile or flow-based ways of working. Most focused on operations and were doing their best with what they knew. But customers weren’t too happy.

The Challenge

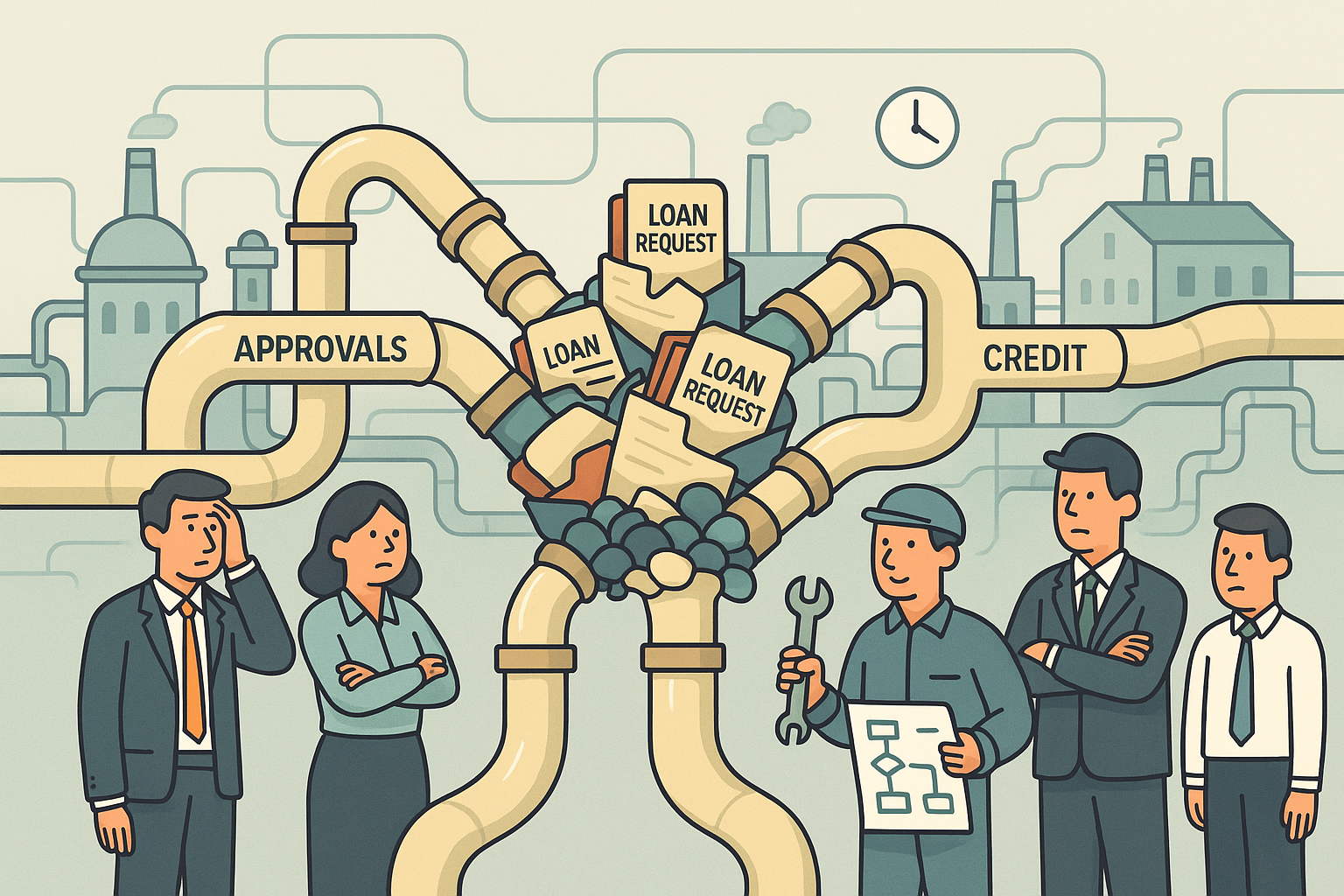

At first, the problem appeared to be “too many approvals and not enough time.” But the real issue was buried in how the work actually flowed. With less visibility on how much work was in progress, no one knew what was stuck or where. Work items were passed between people like a relay race, but without a designated track, causing considerable confusion. Everyone kept switching between different customer deals without closing, trying to help out wherever the fire seemed hottest. The result was constant context switching, longer queues, and eventually burnout. People were exhausted, frustrated, and sometimes taking unplanned leave because it just didn’t feel sustainable.

Dealing with Difficult Stakeholders

One of the biggest hurdles wasn’t fixing the process but getting people to believe change is possible. Most never even heard of Agile, and a few leaders thought it was ‘just a software thing’. Their first reaction was pretty honest: “We don’t build apps, so how’s this going to help us approve loans faster?”

I realised pushing processes or frameworks would only make things worse. So instead of starting with frameworks, I began by explaining why Agile exists at all. We talked about what slows the work down, hand-offs, rework, queuing theory and how visibility and feedback loops can fix that. We didn’t talk about “stand-ups”, three golden questions or “retros.” We talked about what those things solve, which included making blockers visible, reducing rework, and learning faster. Once they saw how it could cut waiting time and make their lives easier, the tone shifted from “another new thing from management” to genuine curiosity.

The difficult part wasn’t attitude; it was their belief system. They weren’t fighting the change; they just couldn’t see how it connected to their goals. Once that link was clear, resistance faded with nudges along the lines. People who once questioned the need for Agile ended up running daily flow sessions themselves.

Step 1: Understanding the System

We kicked things off by mapping the entire loan approval process, right from the time a request came in until the funds were released. It was a messy session that took a few tries. We used value stream mapping to see every step, every approval, and every delay. Wherever we saw the opportunity to digitise in terms of application form storage and signatures, we flagged it out and pondered upon it later. We were ruthless in cutting down the cycle times and idle times. When we finished, the team could finally see why things took 60 days. Work was sitting idle between approval cycles. Queues were forming everywhere. That exercise did more than just give us data; it made people curious. Once they saw the problem with their own eyes, they genuinely wanted to fix it. It also gave them pride to be part of the process, which helped build ownership.

Step 2: Building Trust Before Process

Before we changed how they worked, we had to build trust. We ran a Personal Mapping session (a simple tool from Management 3.0) where people shared a bit about themselves what they enjoy, their families, hobbies, and goals. This was also tweaked a bit to prompt them with role related and decision making process. That broke down silos fast. Suddenly, the “approval specialist” wasn’t just a name on an email but someone you understood. This built empathy. After that, we created a social contract the team’s own agreement on how they wanted to work together, handle pressure, and communicate when things went wrong. It sounds soft, but it made everything that came next possible.

Step 3: Making Work Visible

The next big step was to make the invisible visible. We created a visual radiator showing every case, every stage, and who was working on what. I introduced a few simple ideas from queuing theory on why queues get longer, why too much work in progress slows everything down, and how limiting WIP actually makes things faster.

We set up daily sync meetings to talk about what was moving, what was blocked, and what needed attention.

We were measuring the average time the work spent in the respective queues and find ways to bring it down. These weren’t traditional , “stand-ups”, but were quick, practical syncs focused on flow, not status. For work that was planned, we had weekly planning. For ad-hoc urgent requests, we adjusted daily. Over time, the team began to run this rhythm themselves. They didn’t need me to practice it and saw how it made their days easier.

Step 4: Scrumban in Action

We didn’t use Scrum by the book. It was more of a Scrumban setup, if it requires a name, short sprints combined with continuous flow. The key was keeping it simple:

- Limit how many loan cases could be open at once

-

Finish what’s started before starting something new

-

Measure batch size within the sprint and queue time and the by product was improved cycle time and throughput

Soon, they could see patterns. When WIP increased, cycle time got worse. When they focused on finishing, work moved faster. The insights were real-time and obvious.

Results

The turnaround was dramatic.

Some Numbers:

- Loan approval time dropped from around 60 days to 21 a 65% reduction.

- Throughput almost doubled, from 7 deals to 13 per cycle.

- Predictability improved, and queue sizes became manageable.

Culturally

- People were less stressed, and one of the indicators was unplanned leaves dropped.

- The team started to make improvements.

- Two team members stepped into new leadership roles, one as Product Owner (refer to the recommendation), one as Scrum Master.

- The leadership team noticed the shift, too. What started as a trial “agile experiment” became a model for other lines of business.

Reflection

What stood out most from this journey was how much change depends on people before process. It’s always a balance. The frameworks give you structure, but trust and relationships make it real. In this case, starting with people worked. Taking a curious, listening approach built safety and opened real conversations about what wasn’t working.

We didn’t start with the Scrum Guide or sprint ceremonies. We spoke about the sticky issues, for eg, the hidden queues, constant switching, and lack of visibility that made good people feel like they were failing. Once they saw how the system created their pain, they began to own the fix.

The Scrum Guide says “follow to understand,” but it is not enough on its own. People don’t follow process; they follow purpose. When you help them see that purpose, and the system behind their struggles, they’ll move faster than any framework can force.