Product Owner: I’m going to share the high-level goals with you as user stories.

Business Analyst: Sounds good. Should I take your draft and start breaking it into stories in Jira?

Product Owner: Great idea.

…(Inner voice, BA): How do I know these stories actually reflect what users care about and not just what the PO thinks they care about?

…(Inner voice, PO): We’ve done the competitor analysis and research. I’m confident we know what the market wants.

Business Analyst: Alright, I’ve added all the features to the backlog and mapped them as user stories.

Product Owner: Perfect, that’s progress.

…Business Analyst (Inner Voice): Progress toward what though… shipping or solving?

A week later

Product Owner: Let’s build fast, get feedback, and pivot if needed.

Business Analyst: Sure. Though I wonder if we’re validating the right thing.

Product Owner: That’s what the data is for. If engagement goes up, we’re on track.

Business Analyst: Which metric exactly?

Product Owner: The one that goes up.

——————————————————————-

Product Owner: Can we document the acceptance criteria thoroughly?

Business Analyst: Of course. We can craft it perfectly.

Developer (quietly): Yes, we need everything perfect. Definition of Ready is important.

Tester: If you change the ACs halfway, we’ll need them amended before we start.

Developer: Yes, that’s true.

…Scrum Master (inner voice): Perfect. That word is familiar. Every extra hour we spend polishing these ACs adds transaction cost through reviews, clarifications, and sign-offs. But the real penalty is delay. The longer we wait to test an assumption, the higher the cost of delay if we’re wrong. We think we’re buying certainty, but what we’re really buying is slower learning at a premium price.

The Common Pattern

The above pattern that plays out in almost every product team. Everyone is busy, confident, and doing things right on their part and yet the whole system lack the benefits. And, the product teams end up in a spiral loop of chasing outputs mandated by the leaders. The assumption is always the same: we’ll build, test, learn. How often we adjust from what we learn ? We keep optimizing the system instead of eliminating as a mindset. The hidden cost is that we start learning after the damage is done. Most organizations aren’t afraid of being wrong. They’re afraid of being seen as wrong. So discovery becomes a series of polite handoffs, a step garden of assumptions passed from one role to another until the real problem is buried under tracking tools.

What’s really happening is handovers and building the wrong thing faster. It’s the compounding cost of coordination. Our distance to the source, the real consuming stakeholders (eg: real users) keeps growing. By the time information reaches the team, it’s been filtered through layers. The result? The feedback loop that’s supposed to accelerate learning ends up slowing down.

The Outcome Trap

Most agile product teams don’t start with the end in mind. They start with ideas, functional requests, and tickets. A support issue sparks a feature. A stakeholder comment becomes a story and every story is the priority. A competitor move becomes a must-have.

To look agile, teams wrap this in the language of experimentation:

“We’ll build a quick MVP and add to it later.”

But here’s the catch: most MVPs aren’t experiments at all. Most teams don’t use MVPs to learn; they use them to start building sooner. So instead of testing assumptions, they just build smaller versions of the bigger wrong idea. MVPs should reduce the cost of learning. Most only reduce the cost of building. The risk stays exactly where it was, just spread across more sprints. They call it validation when it’s really confirmation.

Validation is about making your assumptions visible and testing whether they could be wrong. Confirmation is about finding comfort that you were right. The difference is bias. One reduces it by mapping and testing assumptions. The other feeds it by searching for supporting evidence.

Most of the organisation is stuck in a loop of the following:

Idea → Build small → Ship → Measure activity (Mostly optional)

Outcome-driven Approach:

Most of the outcome driven thought process starts with the following:

Assumption → Test small (riskiest ones) → Measure learning → Decide next step

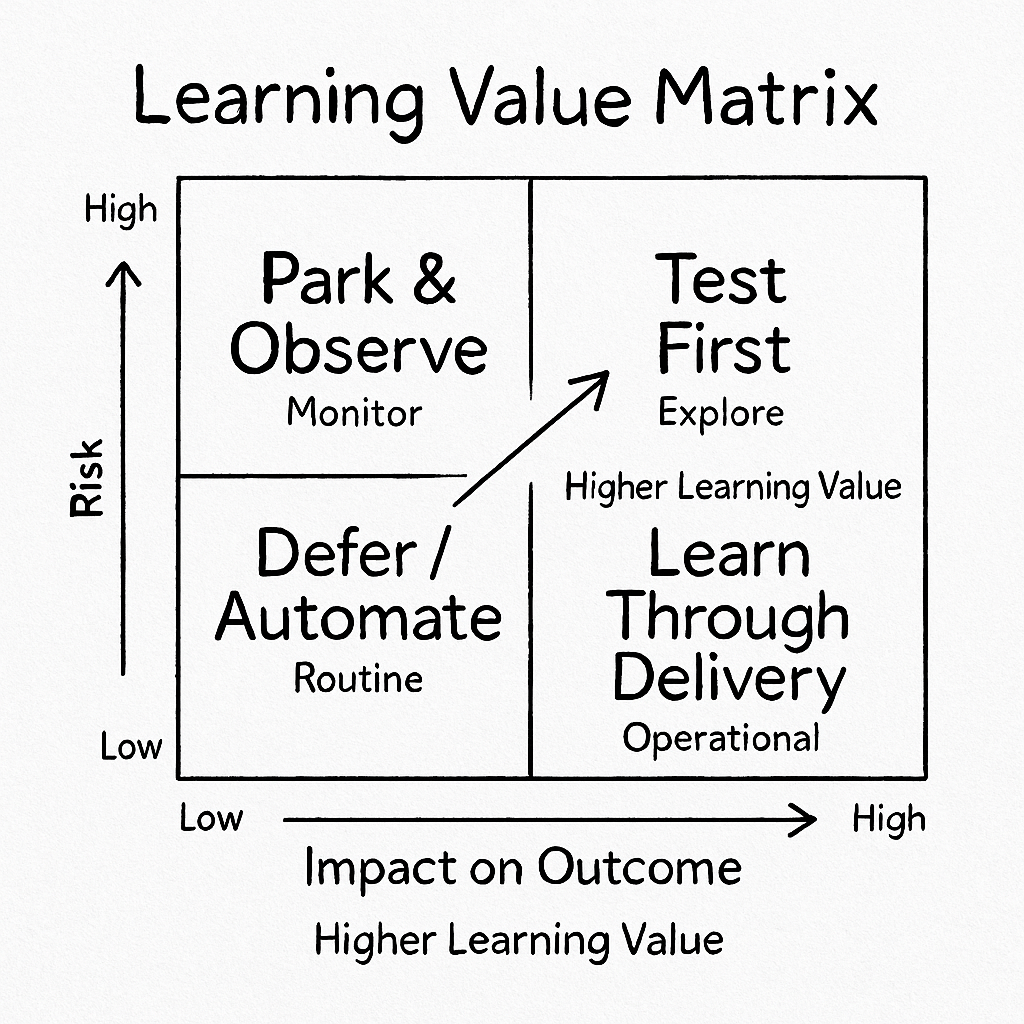

The first accelerates output. The second accelerates truth. Teams often shrink the scope of delivery but not the scope of uncertainty. Tools like MoSCoW make this worse. They help you decide what to build first, not what to learn first. An alternative approach aligned with “Through minimum create maximum” at Nimble Minds is map your assumptions. Test the riskiest and most impactful ones first. Stop sequencing by output importance. Start sequencing by High risk and high impact. That’s how you actually de-risk the work. Below is the learning canvas, I generally use as an anchor point to guide such conversations strategically.

A Thinking Pattern (For Crafting Your Product Goals)

The above canvas helps teams see how to sequence their product goals based on risk and impact.

Not all work teaches you something. In the bottom-left, Defer or Automate covers the low-value work based on risk profile- things you can delay for later. They don’t move the needle, and they don’t teach you much. Park and Observe is where you place ideas that are risky but low impact ; interesting to watch, not worth chasing yet. Learn Through Delivery is proven, high-impact work. You already know it creates value, so the learning comes from refining and scaling what works.

The real action is in the top-right – Test First. This is where the unknown meets the important. Experiments here have the highest learning payoff because they reduce uncertainty fast.

The arrow from bottom-left to top-right shows the journey from routine work to real discovery. As both risk and impact rise, so does the value of learning.

The matrix helps teams stop asking “What should we build first?” and start asking “Where should we learn first?” – that’s where progress begins. High-risk, high-impact work carries the highest cost of delay in knowledge work. Every day you postpone learning here, you accumulate risk debt that compounds across the system financially, operationally, and strategically.

How It All Ties Up

Make outcomes explicit early. If you can’t describe the change in behaviour or value, you’re planning delivery, not discovery. If you started with outputs, take a diagnostic approach and connect them back to outcomes. Trace every story to a measurable outcome both to product and organizational goals. Run discovery continuously. Launch day isn’t the end; it’s when your assumptions finally meet the real world.

Starting With the Outcome

When you start with the outcome, ask simple questions:

“What change in user behaviour or business value do we want to see?”

For example: Increase daily active listening time by 20%. This anchors discovery in impact, not activity. It keeps the team aligned on value, not features. It makes prioritization clearer because every idea faces the question: Does this move the needle?

The challenge is that outcomes are often broad. Increase engagement sounds nice but tells you nothing about what to build or measure. That’s where Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) comes in – it defines progress in the user’s world so you can design solutions that are means for the consumer to make them progress. Modern agile requirements suggest we need to be accepting change in satisfying the needs of the stakeholder. There is no harm in accepting the change if we are still true to the overall objectives of the product goal.

The Playlist Trap

Very Often there are feature request like : Let’s build a Smart Playlist that recommends songs based on mood. That sounds purposeful and user-centered, but how do we know if it truly moves the user toward progress? Unless you unpack it, you’re still in the feature factory mode. The main job of the listener isn’t to use a playlist. It’s to stay emotionally connected and focused through music during times, without friction.

I would like you to consider this as a clear distinction. A feature exists inside your product. A job exists inside the user’s life. When someone opens Spotify or Apple Music, they’re not saying I want to use a playlist. They’re saying I want to feel good maybe focused, uplifted, or calm and music is the means that helps them achieve that. The playlist is just one of many ways to do it. When the playlist fails, people switch context in their lives maybe another app, background noise, silence, or even humming to themselves. That tells you the playlist isn’t the job. It’s only one way of completing it. You don’t guess the job.

You observe behaviour across contexts and this context is exactly what user stories miss. Watch what people do, not what they say. Some research techniques miss this point. Music listeners switch playlists when their energy changes. They stop listening when the music no longer matches their mental state. They use music to manage emotion and focus. That pattern of music as a tool to regulate mental state is the real job.

To test if you’ve found the real job, ask yourself:

- Does this job exist even if my product doesn’t?

- Do people use different solutions to achieve it?

- Does success look like progress, not interaction?

If all three are yes, you’ve found the true job. Underneath that main job are smaller micro jobs, the individual steps people take to make progress. Knowing the main job tells you the purpose of progress, not the path. If you treat the job as linear, you risk reducing it to “steps in your product.” That’s the same trap as user stories. To understand how people move toward that progress and where they get stuck, what slows them down, and how your product could help, you need to unpack the job into its smaller steps.

That’s where micro-jobs and the job map come in.

- Micro-jobs are the smaller tasks and decisions that make progress happen. They reveal friction and moments where the user struggles, hesitates, or wastes effort.

- The job map organizes those micro-jobs into a structure. It shows the order of progress: what comes first, what depends on what, and where the biggest breakdowns occur. If the main job is the destination, the job map is the journey that leads there. System practitioner could effectively use this to map the dependencies within the process to improve the flow of product development.

Typical actors (varies by org):

- Legal – owns compliance documentation

- Product – owns the flow and UI/UX

- Marketing – owns messaging (maybe pre-login)

- Dev/UX – implements front-end/backend logic

- Customer success – provides clarity and context

Each of these stakeholders within the organisation would take the job map and identify actions on their side. Primarily, what each stakeholder must do to remove the friction i.e., how they contribute to value. The output from this exercise is a different sequence of value map based on the constraints of the organisation.

Quick Recap on what we covered so far :

- Always start with outcomes and measurable objectives. Negotiable on scope not objectives

- Use Jobs to uncover the outcomes or the “Why” as well as to clearly see the progress towards objectives

- Break down the main job

- Use Job map to organize micro jobs and also to see the friction in achieving the progress

- Layout the job map over your organization capabilities (in scaled organizations) for faster product development flow

- Sequence them based on dependencies and high risk to achieve high value in the shortest possible time

- Run continuous discovery and not a stage gated process

Note: At Nimble Minds, we use this same repeatable approach to help teams diagnose friction, connect discovery to delivery, and focus on measurable progress.

- Can listeners identify their mood?

- Do they want music chosen for them?

- Do they trust the app to capture their vibe?

Then they’d run small, low-cost tests to see if those beliefs hold. A simple Feeling Bored? button could tell you in days whether users even want that kind of help. That’s the difference. Confirmation protects belief. Validation tests it.

When to Use User Stories and When to Use Job Stories

- Use User Stories when the problem space is already validated, minimal to discover or when scaling a proven product.

- Use Job Stories to discover whether the solution is needed in the first place.

For example: As a listener, I want my playlist to detect when my energy drops; so that I can stay focused without switching manually.

You can make that explicit by defining what “done” looks like in terms of progress.

- The system detects a drop in engagement (skips or pauses) within 10 seconds.

- It adjusts the playlist automatically.

- The listener continues playback for at least 15 more minutes without switching manually.

That’s how you bring job thinking into day-to-day work without rebuilding your requirement capturing process. You don’t need to replace user stories with job stories. You just need to make sure every story connects to real user progress, not just product activity.

Key Takeaways

• Most teams talk about outcomes but still chase outputs. They optimize speed, not learning.

• Building smaller doesn’t make you smarter it just makes you wrong cheaper.

• The real goal isn’t to shrink scope; it’s to shrink uncertainty.

• Confirmation protects belief. Validation tests it

• Focus learning where risk & impact are highest; that’s where progress pays off.

• A feature lives in your product; a job lives in your user’s world.

• True outcome focus begins when learning happens faster than delivery.