Product Leader: I would like to carve out the MVP for the project.

Delivery Person: What’s the end objective?

Product Leader: In a nutshell, I want to replace the current CRM with Salesforce and let the legacy system continue talking to Salesforce.

Delivery Person: Let’s review the backlog entries you’ve marked.

Product Leader: Sure. I’ve spoken to stakeholders and they want everything mentioned in the backlog. To start, we’ll just take the Must Haves and Should Haves as the first cut.

Product Leader: Oh, this is a big project. Let me break it into MVP 1, 2, and 3 so we can get things out the door within time and budget.

Delivery Person: That’s a good start, but how will you know if the first release meets what stakeholders actually need?

Product Leader: We’ll get feedback fast without fancy stuff in the first release.

What’s the common pattern in both?

We used MVP to get feedback on something mediocre quickly. While fast feedback is valuable, most of the time we don’t define what success looks like. So what do we actually do with the feedback? We drift away from learning the moment someone says, “Let’s break the big project into MVPs.”

The question was never: “Do we need an MVP or a full-featured solution?” or “How do I break a big project into smaller scopes?”

The real question should be: “What’s the riskiest assumption we’re making, and how can we test it quickly?”

That reframes MVP as a risk-reduction tool, not a scoping shortcut.

Let’s go back a bit and know what MVP is.

The story of the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) started in 2001 with Frank Robinson. He described MVP as the smallest thing you can build that delivers value and starts the learning process. The idea was to deliver maximum value in the shortest possible time. Then came Eric Ries and The Lean Startup, which made MVP mainstream through the build-measure-learn feedback loop.

Fast forward to today.

Teams throw around terms like MVP, MLP, and MMF and wait for it, I’ll add a new one at the end. But here’s the problem: most have fallen into the trap of output. Instead of using MVP to learn, they treat it like a checklist of features. The focus has shifted from discovery to delivery.

“Minimum” quietly turned into “not good enough is fine for launch.”

“Viable” became “good enough for the user,” which narrowed the lens and left out other stakeholders who matter just as much. And viable for whom, exactly? When “viable” is vague, teams optimise for what’s easiest to show, sliding straight into the build trap.

Don’t get me wrong, delivery is important. That’s when reality gives you feedback. But the real question is: how often do we actually course-correct or measure whether what we built was truly needed by all stakeholders, not just users? It’s become about getting something, anything, out the door as fast as possible, even if it’s half-baked. The result? Stage-gated, linear thinking. You’ve got the full product vision, but you release a small piece of it and call it “MVP.” Once you start building, the act of building becomes the goal. To avoid failure, we pile on more features to protect ourselves, yet that never guarantees success. We end up measuring success by how much we’ve shipped, not what we’ve learned.

The visible symptom is teams chasing speed. The deeper cause isn’t speed, it’s the confusion between shipping and feedback. Teams assume that because they’ve released something, they’ve learned something. But shipping isn’t learning unless it produces insight that changes understanding or behaviour.

The problem isn’t the desire for speed; it’s what we measure as feedback. Most teams look at deployment, not discovery. They optimise for visible movement, story points completed, story counts closed, and features shipped without asking whether the system is actually helping users get their job done or enabling them to make progress in solving their problem.

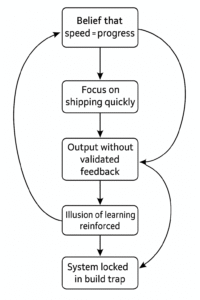

The real causal chain looks like this:

- Belief that speed = progress

- Leads to focus on shipping quickly

- Which creates output without validated feedback

- Which reinforces the illusion of learning

- And locks you in a build trap

That’s the deeper issue. MVP encourages linear product thinking you move from one version to the next as if learning happens only through sequential output. But real learning isn’t linear; it’s systemic. You can’t slice a product into smaller parts and expect it to reveal value. Value emerges from how those parts work together to help someone make progress.

That’s where MVE (Minimum Valuable Experience) comes in. It shifts the lens from product to experience.

It asks: What’s the smallest complete experience that allows the user to feel progress in their job to be done?

Instead of cutting features, MVE encourages looking at the outcome as vertical slices thin, end-to-end that cross design, logic, and interaction layers. Each slice is a coherent experience where the user completes part of their job, and you get to see how the system behaves.

That’s the real shift, you’re not slicing for scope, you’re slicing at all levels, starting from outcome. Each slice becomes a learning instrument, not just a deliverable. Using the Jobs to Be Done lens, MVE helps you see what the user is trying to accomplish and design minimal experiences that test how well the system supports that progress. When you think this way, you start seeing cause and effect differently. Every experience becomes feedback.

MVP was always meant to be about learning. But somewhere along the way, we forget why it mattered. Learning drives behaviour change; shipping is just an action. Maybe it’s time to return to that original spirit, but with a more holistic, experience-driven mindset that sees products as living systems built to help people make progress, not just smaller things to build faster.

If you ever wonder why there’s room for yet another acronym, it’s simple: clarity of language changes focus. Perhaps that’s why we have so many different acronyms. If you interpret MVP the way it was meant, not as faster shipping, but as faster learning, you certainly don’t need MVE.